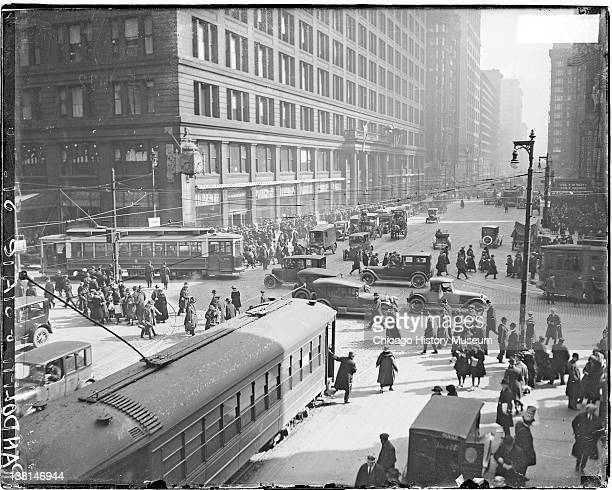

In 1920 Chicago was a city of 2.7 million souls, swollen with returning Great War veterans, Eastern European immigrants and Black migrants from the South. The city gained a reputation as an area of tumult, corruption and violence. In July 1919, rock-throwing white teens murdered a Black child swimming at a segregated beach, triggering a weeklong race riot that resulted in 38 deaths and initiated a nationwide Red Summer. The city was scandalized by the Black Sox Scandal, the revelation that the Chicago White Sox threw the World Series for gangland money; its players were banned from baseball while the gamblers who arranged it escaped prosecution. And already the brutal Prohibition wars took shape, with bootleggers Johnny Torrio, Dion O’Bannion and Big Jim Colosimo staking out rival claims across the city.

Carl Otto Wanderer, in contrast, was just another American trying to make a living. He grew up in Chicago and helped his German-born father run a butcher’s shop; his childhood was darkened by his mother’s mental illness, which resulted in her committing suicide. Enlisting in the Army, Wanderer saw heavy action as a machine gunner in France, earning several decorations and the respect of officers and comrades; his company commander called him “alert, intelligent, very competent, brave, a good soldier.” One writer said that Wanderer “never lied…never drank, never smoked, never chewed gum”; in appearance he was tall, thin and at just 23 prematurely balding. The quintessential square, or so it appeared.

Wanderer held a torch for Ruth Johnson, a pretty childhood friend who sang in their church choir. They began courting before the war, with Johnson promising to remain faithful to Carl, spurning the affections of other men at the church while he served overseas. When Wanderer came home with a chest full of medals and a second lieutenant’s bars on his shoulders, he seemed an even more appealing catch. They married in October 1919, and Ruth was soon expecting their first child. “We never quarreled,” Wanderer would insist, adding that “I’ve always done what was exactly right and never done wrong.”

Carl and Ruth moved into the Johnson family home on North Campbell Avenue, hoping to save money so they could buy a house before their child arrived. At home, Carl played the dutiful husband and father, commuting between his father’s butcher’s shop and their apartment. Ruth’s mother Eugenia recalled that Carl and Ruth spent “night after night…together, happy, loving and talking about the baby.” If Carl sometimes came home a few hours late, they readily accepted his explanations about late hours at the shop or needing to run errands for his wife.

On June 21, 1920 the young couple went out to see a movie, The Sea Wolf. On the way home, Ruth told Carl that she sensed that they were being followed; Carl assured her that he was carrying his service pistol, a Colt 1911, and that they had nothing to worry about. They’d reached their apartment, with Ruth fumbling for the housekey and announcing she was going to turn on the light. “Don’t do that,” another voice barked. They turned, and saw a “raggedy stranger” with a handgun who demanded their money.

A flurry of gunfire rang out in the alley, lasting several seconds. Eugenia Johnson waited until the shooting stopped, then rushed outside. To her horror, she saw Ruth, eight months pregnant, bleeding from two bullets in her chest. “My baby is dying,” she moaned as she lay dying the payment. Next to her, Carl stood over the body of the would-be robber, having shot him four times. “No one will hurt you anymore,” he told Ruth, cradling her head helplessly as she passed away.

It was a scene from a lurid paperback, a noble war hero trying to defend his pregnant wife from a disheveled malefactor. The press fell over each other to praise Wanderer’s doomed courage; the police, too, were impressed. “I thought he was entitled to a medal for bravery,” admitted the officer who questioned him. Eugenia Johnson recalled that Carl seemed “to be greatly affected when I tried to comfort him.” To all appearances, his grief was as sincere as his heroism.

Still, suspicions began to fester. Charles MacArthur, crime reporter for the Chicago Herald and Examiner, was struck when police reported that the “ragged stranger” (his identity unknown) carried a .45 caliber service pistol identical to Wanderer’s. Surely, if the man was so down-and-out, he could easily have sold such a weapon rather than engage in a risky hold-up of a man known to carry a sidearm. A friend on the police force provided MacArthur the serial number to the robber’s weapon. He did a cursory check and discovered that the pistol had been purchased by a man named Peter Hoffman, who subsequently sold it to…Fred Wanderer, Carl’s cousin.

MacArthur tracked down Fred, a Chicago mailman, and asked him about the weapon. Fred confirmed that he had purchased the lightly used pistol from Hoffman for $7.50. When the reporter asked what became of it, Fred told him that he had loaned the weapon to Carl one day before the shooting. “When he realized the implication of such information,” Jay Robert Nash writes, “the cousin collapsed in a dead faint.” His editor, Walter Howey, dutifully relayed this confession to the police.

The police assigned Sergeant John Norton, of the newly established Homicide Bureau, to investigate. Norton began by tracking down the identity of the “ragged stranger.” After numerous false starts, Norton discovered that he was a Canadian named Al Watson who had served in the British Army during the war, made his way back home and drifted into vagrancy. This solved one mystery, but didn’t explain what happened between Watson, Carl and Ruth in the alley.

The next piece came courtesy of another reporter, Ben Hecht of the Daily News. Hecht shared his friend and rival MacArthur’s suspicions, which were enhanced by a brief and hostile interview with Wanderer. When Hecht commented that it seemed suspicious that Wanderer hadn’t been able to outdraw the “ragged stranger,” the husband lost his temper and showed the reporter the door. 1 Hecht discovered through Wanderer’s family friends that Ruth had withdrawn $1,500 from a savings account soon before the murder. Still circumstantial, the evidence nonetheless began pointing towards an unsavory conclusion.

In early July, Sergeant Norton arrested Wanderer for questioning. Despite prolonged badgering from Norton, several officials from the coroner’s office and even MacArthur’s Herald Examiner colleague, Harry Romanoff (police and press, in those days, had a bizarrely symbiotic relationship), Wanderer confessed to very little. He assured police that the guns were simply a mix-up; he admitted that Ruth had withdrawn the money, but suggested it was in preparation for the child’s birth. When Wanderer’s attorney arrived, the suspect clammed up, but police refused to release him until they could clear up these discrepancies.

The dogged Sergeant Norton finally cracked the case. While visiting Wanderer’s apartment, he found photographs of Wanderer with a number of young women at fairs and amusement parks. Most damning of all, however, was a letter from Wanderer he discovered, written after Ruth’s death to a girl named Julia. “Sweetheart,” it read, “I am very lonesome tonight,” suggesting that his beloved bring her friend Hilda over for a threesome. Noticing that several of the photographs featured the same girl, Norton guessed this was Julia and returned to the police station with a bluff.

To avoid suspicion, Norton sent Harry Romanoff to speak with Wanderer. “Julia sent me,” the reporter announced; “she’s coming to see you.” Wanderer lost his composure, asking Romanoff to stop her and blurting out her phone number. Norton dialed it and arranged a meeting with Julia, who turned out to be a 17 year old secretary, Julia Schmitt. Schmitt told Norton that she had met Wanderer six times, and while they had never engaged in sexual activity, his interest clearly wasn’t platonic. “He said I was his only friend,” Schmitt recalled. “I told him I could never think the same of him.”

Faced with such evidence, on July 9th Wanderer finally confessed. He admitted that he had grown tired of Ruth and was enjoying a second life as a footloose ladies man. Asked about Julia, he said “she was just like a lot of other girls who came into the butcher’s shop” and that, despite his letters, he had no particular attachment to her. Indeed, he appeared more interested in returning to military service (a subject, police confirmed with Wanderer’s friends, he had often raised in the months leading up to the murder). More shocking was the elaborate murder scheme he unraveled, in a handwritten, twenty page confession for police, fitting together his domestic dissatisfaction with his wife’s death.

Having decided to do away with Ruth, Wanderer encountered Al Watson smoking a cigar outside a hotel on Madison Street a few days before the shooting. Struck with inspiration, he offered the “ragged stranger” a $25-a-week job as a truck driver if he’d help Wanderer with his own problem. Wanderer offered the man a further bonus if he would fake a hold up with Carl and Ruth to prove his bravery to his wife. If Watson, homeless and unemployed, harbored any reservations about this bizarre scheme, he kept them to himself.

As explained to Watson, he would meet Wanderer on their doorstep, demand some money and be given a small amount of cash, then they would stage a fight for Ruth’s benefit. Wanderer told Watson he would hand the vagrant an unloaded gun, threaten him with his own, also unloaded pistol and hopefully impress Ruth with this mock-heroic dumb show. Instead, when Watson arrived Wanderer drew both (very much loaded) handguns and shot both him and Ruth simultaneously, then planted cousin Fred’s weapon on the vagrant before Ruth’s mother arrived.

The story was almost too elaborate to believe; Eugenia Johnson admitted that “I should never have believed it if Carl hadn’t confessed.” But Wanderer, who said that “nobody knows me…unless I tell them,” felt no remorse over murdering his wife or unborn child, and certainly not the “ragged stranger.” After all, he had worked as a butcher and served in the military. “The thought of killing anybody doesn’t bother me as much as it would the average person,” he admitted.

That fall, with the courtroom packed by reporters from across the country, Wanderer was tried on two counts of murder. Incredibly, despite the ironclad case presented against Wanderer he was only convicted on a charge of manslaughter for Ruth’s death, receiving a maximum of 25 years for Ruth’s death. Though Wanderer’s attorneys tried to present him as insane during the trial, after hearing the verdict he made no effort to hide his jubilation. “I knew I’d never swing,” he chortled to friendly reporters.

Chicagoans were outraged by the verdict, which was denounced by reporters and politicians alike. John Norton, promoted from Sergeant to Lieutenant for his work cracking the case, grumbled of Wanderer “that bird should swing, if ever a man should.” Robert Crowe won election as Cooke County’s Chief Prosecutor that fall by proclaiming the verdict a travesty, promising that if elected he would “force Wanderer to trial for a second time.” Crowe won, and managed to stage a separate trial for the murder of Al Watson.

This time, the outcome was ordained. Wanderer’s attorneys pressed the insanity plea, further insisting that the police had beaten a confession out of him (hardly implausible in that time and place, though Wanderer was accompanied by a lawyer for most of his interrogation). Crowe’s thundering summation – telling jurors that Wanderer provided “kisses for Julia, bullets for Ruth” after reading one of his letter in court – carried the day. After two months of testimony, in January 1921 Wanderer was sentenced to death for Watson’s murder. Crowe announced that “justice has been done and a great error has been corrected.”

Wanderer went to his grave characteristically defiant. “I ain’t afraid to die,” he insisted; “I fought in France.” Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, who often visited him in prison, convinced Wanderer to sing “Dear Pal O’ Mine” as he mounted the gallows. On September 30, 1921 Wanderer obliged, reaching the song’s chorus before his neck snapped. From the gallery, MacArthur turned to Harry Romanoff and commented, “that son of a bitch should have been a song plugger.”2

However much Carl Wanderer and the Ragged Stranger captivated Chicagoans, their notoriety was short-lived in that decade’s “Murder Capital of America.” Robert Crowe gained greater notoriety a few years later persecuting Leopold and Loeb, which easily supplanted Wanderer in the national consciousness. Chicago’s frontpages were soon afterwards splattered with gangland shootings, racial violence and other elaborate killings that made Carl’s “bullets for Ruth” seem like child’s play.

Sources and Further Reading

This case has inspired numerous contradictory accounts, with distortions provided both by the participants and later writers, especially the reporters who embellished their own roles in solving the murders.3 I first encountered Wanderer in Jay Robert Nash’s Bloodletters and Badmen (1973; 1995 updated edition), which can’t be considered reliable, especially on this case.4 Other books consulted, with varying degrees of reliability, include Simon Baatz, For the Thrill of It: Leopold, Loeb and the Murder That Shocked Chicago (2008); Albert Harper, The Chicago Crime Book (1967) and Michael Lesy, Murder City: The Bloody History of Chicago in the Twenties (2007). I attempted to shape a coherent narrative based on the elements of each account that struck me as most plausible and consistent with other evidence.

You must be logged in to post a comment.