Welcome back to Franchise Festival, where we explore and discuss the history of noteworthy video game series from the last four decades. Older entries can be found here.

This week we’ll be reading about the text-heavy Wizardry franchise. This article would not be possible without the extraordinarily in-depth series coverage by Sam Derboo over at Hardcore Gaming 101. I strongly recommend checking it out if you want a more extensive look at the vicissitudes of this long-running saga.

Background

TSR first published Dungeons and Dragons in 1974. This tabletop role-playing game, created by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, would have an immediate and lasting impact. Young people across the English-speaking world were introduced to the concept of fantasy adventures controlled by them and their friends.

In the game, one player takes on the role of Dungeon Master; this person functions as a director, secretly manipulating the map through which characters navigate and controlling non-player characters. All other players design characters, hewing to specific archetypes (e.g. warrior, thief, etc.), and choose their character’s actions. Combat occurs between player characters and enemies controlled by the dungeon master. Dice are the primary means of establishing whether chosen actions succeed or fail. Given the absence of any pre-defined board or pieces, players’ imaginations are the only limit to an adventure’s scope.

Like many American college students in the late 1970s, Robert Woodhead was an enthusiastic participant in Dungeons and Dragons campaigns. He and his friends were so involved with the game, in fact, that he was asked to take a leave of absence from Cornell University due to his low grades. This gave him time to begin learning programming in an attempt to aid his parents’ small business. He branched out into game development from there, joining up with Andy Greenberg, another young man he knew from Cornell. The two would soon be exploring ways to adapt the Dungeons and Dragons experience to a single-player computer environment on the Apple II platform.

Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord (1981)

Wizardry was in development by 1980, but went through extensive beta testing. This was relatively rare in the era, and all the more surprising on a project that largely consisted of two full-time workers. Still, Greenberg had a team of Dungeons and Dragons hobbyists who were more than willing to test each iteration of the beta game and offer feedback. The result was one of the medium’s most polished, complex titles produced so far.

Wizardry allows a player to create a team of six characters, navigate a ten-floor dungeon and battle numerous monsters. Character creation, like much of the game’s interface, is entirely textual. No visual representation of the characters or the town in which the game begins are provided to the player. Like other early text adventures, this is leveraged to offer a level of complexity that would be impossible with the era’s low capacity for visual fidelity. Unlike other early text adventures, players can heavily customize their characters in a manner similar to Dungeons and Dragons – sex, race and morality alignment (good or evil) are selected by the player, then statistics are generated for a number of attributes; these stats provide a foundation for the characters class, which determines the availability of certain skills or spells.

Once characters are created, the player can have his or her squad explore a small town. The town offers a number of shops and facilities, and will function as a home base throughout the player’s quest. It is the only place in the game where progress can be saved, due to a quirk of programming and the lack of remaining space on the disk layers which display dungeon navigation.

Those disk layers are chock full of data because dungeon exploration actually involves a comparatively impressive visual interface. Information about the player’s party is displayed in windows clustered around a small, first-person depiction of the party’s surroundings. The dungeon is devoid of visually represented enemies, instead being rendered as a barren wireframe environment, but this represents a major step forward from text adventures of the 1970s. For the first time, the player had a visualization of the areas he or she was exploring.

Much of Wizardry’s exploration still hinged on player imagination and ingenuity, of course. The dungeon consists of ten floors made up of hallways populating a 20 x 20 grid when viewed from above. Movement occurs through individual steps in four cardinal directions as the player attempts to avoid unseen traps and collect items that open the next floor. Without drafting a map on graph paper, players are likely to become hopelessly lost in a maze of visually indistinct pathways.

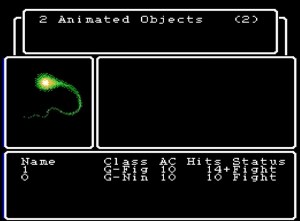

Random encounters are introduced for the first time in dungeon exploration sequences. As the player character’s squad advances from tile to tile throughout the dungeon, there is a chance that one or more monsters will attack. One of the attackers is drawn in the window which otherwise functions as the exploration view. Players and NPCs take turns attacking one another using physical blows, class-specific skills, and spells. In another design choice necessitated by the low memory capacity of Apple II disks, spell names of a particular category only change slightly as the player improves their strength. Some of these spells and abilities also aid in navigation by revealing the player’s coordinates on a given dungeon floor.

One way in which Wizardry is distinct, not only from later titles in the genre it influenced but also from its RPG contemporary Ultima (1981), is the absence of virtually any narrative. The player characters are simply tasked with defeating a wizard named Werdna on the bottom floor of a dungeon. Much of the storytelling, so to speak, hinges on emergent gameplay based on each player’s specific experience. What happens to a party made up entirely of wizards? How nerve-wracking was the struggle to get from Floor 6 back to town for healing? These kinds of scenarios would provide a new and exciting story for each individual player.

At the same time, progression systems set a new standard for character development. Dungeons and Dragons had featured leveling mechanics since 1974, but this was still novel in the world of video games. Woodhead and Greenberg adopted the leveling system fully from their primary influence, introducing the ability to improve character skills by gathering experience points; these experience points are acquired when the party defeats a group of enemies. As characters level up, they enhance their attributes and gain access to new skills or spells. Once specific attributes are improved enough, the player can transition his or her characters to new job classes which depend on higher stats than those available at Level 1.

Players grow attached to their parties over the course of lengthy gameplay sessions. Due to the idiosyncratic layouts and traps that might teleport or instantly kill a party, runs on the dungeon might last dozens of hours. By the end, players would rarely be willing to part with the team they had shepherded through Wizardry’s titular Proving Grounds. Happily, Woodhead, Greenberg and publisher Sir-Tech were eager to capitalize on their fans’ desire to continue the adventure – parties could be exported for use in Wizardry’s sequel.

Wizardry was an underground success when it released first at the 1981 Applefest convention event bearing a slightly different subtitle, Dungeon of Despair; which was changed shortly thereafter at the request of Dungeons and Dragons founder Gary Gygax. The reception was even more positive when it released in general distribution later that year. Critics claimed that it was the most successful recreation of tabletop RPG mechanics in a digital format, even if lacked the rich storytelling potential of its source material. Combat was engaging and the challenge was sufficiently high without feeling insurmountable. Players’ ability to generate their own party of adventurers was especially lauded. A version produced for the Nintendo Entertainment System even offered a more robust visual experience, with the dungeon hallways being reproduced with colors and rudimentary sprites.

Quite a bit of Wizardry’s polish is, admittedly, a result of its iteration upon a couple of already-sprawling niche dungeon crawlers from the 1970s. Oubliette (1977) had been developed as a multiple user dungeon (MUD) using the PLATO programming framework four years before Wizardry’s release. Many elements of Wizardry are present here, including a heavy level of character customization and first-person navigation of a wireframe dungeon. Due to its limited availability – prior to a 1983 Commodore 64 remake it was accessible almost exclusively by American university students – Oubliette would forever lack the popularity and prestige of Wizardry.

The menu-based town interface of Wizardry, on the other hand, seems to have been influenced by avatar (1979), another Dungeons and Dragons-inspired dungeon crawler. Neither of these titles were credited explicitly by Woodhead and Greenberg, but their innovations were a key step in the evolution of game design that made Wizardry possible. The primary difference between Wizardry and these games, played almost exclusively by young college students making use of their universities’ computer networks, is a level of polish and sophistication that fostered mass market appeal.

The pioneering RPG would lead to a long-running series in the United States, but its greatest influence would be overseas. It was one of few American titles localized for the Japanese market, marking the first time an RPG was published in that region. Dungeons and Dragons hadn’t yet penetrated Japan, likely due to the high level of effort involved in translation, so Wizardry was the nation’s first exposure to role-playing systems. Consequently, it inspired an entire generation of young developers with its potential for complex systems-based adventures. Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest, standard-bearers for the Japanese role-playing game sub-genre for the following three decades, would build directly upon the foundation of Wizardry.

Wizardry II: Knight of Diamonds (1982)

Sir-Tech would release another Wizardry game the following year. Given the short turnaround time, it is unsurprising that Woodhead and Greenberg would hew closely to the template established by the series’ debut. Disappointingly, this would manifest in certain elements – like the town and its constituent shops – being entirely identical to the previous game.

Gameplay mechanics, too, are unchanged. Wizardry II’s narrative features the most significant alteration. Rather than being a handful of party members assembled to recover a lost artifact from a dungeon, players take on the role of the victorious adventurers from the previous series entry. The lord who had sent them into the Proving Grounds, unhealthily obsessed with the defeated wizard Werdna, had killed himself following the first game’s conclusion. In the instability following Lord Trebor’s suicide, a new government took over the region. Unfortunately, the royal family of that new government was assassinated by a usurper with the assistance of a monster army. Two members of the royal family escape and enlist the aid of esteemed adventurers in pursuit of an artifact which will re-establish the kingdom’s safety.

The adventurers must travel through a grid-based dungeon, exploring six floors and attempting to recover six pieces of a suit of armor. This armor formerly belonged to the legendary Knight of Diamonds, and donning it is the only way to safely wield the aforementioned artifact. Unlike the previous game, no dungeon floor can be bypassed en route to the dungeon’s lowest level; each floor contains an armor component needed to save the kingdom. This increase in difficulty is mitigated by the newly introduced opportunity to save while in the dungeon.

Wizardry included an odd feature that shared more in common with contemporary pen-and-paper RPGs than software created for video game enthusiasts: players could only begin the game if they imported characters from a Wizardry disc. Enemy encounters were designed for a party with an average level of 13, so importing a group of characters at a lower level than this would typically lead to disaster. The only way to continue the game, in the event of a total party wipe, would be training a new group of characters in the first game and exporting the new characters to Wizardry II. Though this may have been intended as an homage to Dungeons and Dragons, it functions as a punishingly high barrier to entry for new players.

Still, the game was reasonably popular. Fans of the first title generally enjoyed it as a sequel, since it offered more of the same gameplay mechanics in a slightly new, more challenging setting. Others felt that it did little to iterate on its predecessor and had no appeal to potential new players. As with the first game, Wizardry II would be ported to multiple consoles and computers over the following decade, including an NES edition. Like other ports and revisions of the 1982 release, this version would offer the ability to begin using a party not directly imported from an earlier title; what had been a noteworthy feature on the Apple II could not easily be replicated on other hardware configurations.

Wizardry III: Legacy of Llylgamyn (1983)

The third game in the Wizardry series forms the conclusion to an informal trilogy. Like its direct predecessor, the player must import characters from a previous game; in this case, characters may be imported either from Wizardry or Wizardry II. Rather than allowing players to continue raising these characters from the level they had achieved in earlier games, however, Wizardry III resets imported characters to Level 1.

This game design element dovetails neatly with the narrative, which is presented in an introductory cutscene for the first time; earlier entries had conveyed their plots exclusively through supplementary materials. Wizardry III is set decades after Wizardry II, long after the previous generation’s heroes have retired from adventuring. The player takes on the role of these heroes’ descendants, which are functionally identical in all but their amassed experience points. The new set of adventurers must recover a mystical orb from the dragon Lk’breth, lest their region be fully overcome by a series of natural disasters. Like earlier games, the plot is simple and serves primarily to inform the player characters’ motivation to explore a dangerous dungeon.

Wizardry III’s volcanic dungeon marks a break with the past, as it involves ascent rather than descent. More significantly, some of its six floors are open only to parties with a good alignment, neutral alignment or evil alignment. This development renders alignment a meaningful mechanic for the first time in the series’ history, but makes navigation more challenging than it previously had been. Exploring the entire dungeon is only possible through gaming the system – good characters who attack friendly dungeon NPCs can become evil – or by sending multiple teams of adventurers into the volcano. The game does not typically permit good and evil characters to inhabit the same party, after all.

The visual design of Wizardry III also marks an improvement on its predecessors. Windows convey relevant character information over the wireframe dungeon exploration view, and can be toggled off to offer a larger perspective on the game’s hallways. This is a small iteration, but one appreciated by fans who had tired of the formerly cramped interface.

As with earlier series entries, ports were released across a wide range of consoles and computer hardware over the following 15 years. Wizardry III, in fact, would form the basis for many ports of the entire original trilogy. Its window interface was more user-friendly, and would be adopted in all subsequent versions of Wizardry and Wizardry II. Japan was the recipient of the most ports, courtesy of localization carried out by publisher ASCII Entertainment, including versions released for PC Engine, Famicom, MSX2, Game Boy Color, Wonderswan and the Super Famicom among others; all feature significant visual upgrades and modifications to permit players of Wizardry II and Wizardry III to play without importing party members, and tweaks to combat balance. The only individual game ports released in the West were those on IBM PC, Macintosh OS, NES, Commodore 64 and Game Boy Color. Compilations, which appreciably simplify the process of character importing outside of the Apple II platform and bring each entry’s minor mechanical differences into conformity, were released in various regions on Windows, MS-DOS, Sony PlayStation and SEGA Saturn; the latter two actually feature textured polygonal dungeon design for the first time in the series’ history!

Wizardry IV: The Return of Werdna (1987)

While the vast array of international ports had begun by the mid-1980s, Western fans of the Wizardry series would need to wait four years between the release of Wizardry III and Wizardry IV. Happily, their patience would be repaid with the first significant overhaul that the series had gone through since its 1981 debut. Sensing stagnation, Woodhead and Greenberg had decided to innovate rather than return to mechanics that had remained virtually unchanged across the series’ first three releases.

The player would no longer create a party of adventurers to explore a dungeon. Instead, he or she takes on the role of Werdna. This evil wizard had been sealed away at the conclusion of the first Wizardry entry, and the player is responsible for controlling him as he escapes from his sealed chamber. This turns the game into something of a turn-based strategy title, as Werdna resurrects his minions and orders them to attack teams of adventurers exploring the dungeon.

This is a total inversion from the preceding three games, and indeed from other contemporary RPGs. The player is a villain explicitly seeking to bring ruin to the world by recovering Werdna’s amulet from the overworld. There are no party members, but monsters function as the player’s allies in combat. Spells cast by evil priests are actually necessary to navigate through the dungeon (and even to escape from the initial room in which Werdna awakens), though there are no in-game prompts to convey this to the player. Familiarity with earlier games and monster skills is a virtual necessity, maintaining the prior two entries’ high barrier to entry.

In one of the most exciting twists, the heroic adventurers that Werdna mows down are drawn directly from the data of parties used by players in earlier Wizardry games. Sir-Tech had captured this data when performing a unique service for early adopters of the series: when revisions of the first couple of games were published, players could send their original release discs into the publisher to have their characters moved over to the revised version. After this, the new discs would be mailed to players. Due to the high value placed on character parties by Wizardry fans, this feature had proven quite popular in the early 1980s. Seeing their erstwhile parties depicted as enemies in the fourth series’ entry was icing on the cake.

Wizardry IV would prove to be a commercial disappointment, unfortunately, selling less than any other product created by Sir-Tech so far. Its visual design had not appreciably evolved since 1981, though much of this was down to the technical limitations of the Apple II; Sir-Tech had steadfastly stuck to publishing new Wizardry releases on the now-outdated hardware. Monsters remained colorful and well-drawn, but the dungeons were still black-and-white wireframe environments. The series was only increasing in popularity in Japan as console versions proliferated and inspired countless imitators, but it had been entirely surpassed in Western territories by more graphically impressive contemporaries.

Wizardry V: Heart of the Maelstrom (1988)

Happily, Wizardry’s still-dedicated fan community would not have to wait long for a follow-up. The Return of Werdna, ambitious as it was, would represent an anomaly as the series returned to its roots with a fifth entry. One major shakeup was in the cards, however: Robert Woodhead was replaced by David W. Bradley as Andrew Greenberg’s primary creative collaborator on the franchise.

This alteration would have a major impact on the next Wizardry game. Superficially, Wizardry V is hopelessly married to the series’ earliest design choices – wireframe dungeons and text-based interactions remain the visual mechanism by which the player engages with the game world. Monsters are more lushly rendered, but the game is otherwise largely indistinguishable from its predecessors at a glance. Under the hood, as well, certain elements remain the same as they ever were. Eschewing Wizardry IV’s unique protagonist, Wizardry V permits the player to create six adventurers as he or she had done in the first three series entries.

This is where the similarities end, however. Combat is meaningfully enhanced through a greater emphasis on ranged weapons; spears and similarly long melee tools can reach two rows in combat, meaning that a character in the party’s back row can now attack the enemy party’s front row. Characters wielding these weapons in the front row can strike the enemy party’s back row. Turn-based combat mechanics remain unchanged, but the player’s options are more complex.

NPCs make their debut in dungeons as well. These eccentric characters offer the opportunity for nonviolent interaction even outside of the player’s home base, making dungeon exploration more engaging from minute to minute. Wizardry V offers more writing to support these characters, making it the funniest entry in the series so far. Dungeon floors simultaneously integrate more puzzles, offering an experience even more reminiscent of a proper Dungeons and Dragons campaign than earlier Wizardry titles had been.

Interestingly, much of the game’s unique approach to dungeon exploration can be attributed to its origins as a distinct IP. Bradley had begun development on a game called Dragon’s Breath before being hired by Sir-Tech, and he simply adapted this concept to Wizardry’s pre-existing framework while the company was otherwise occupied developing the series’ fourth entry. Wizardry V would be finished by 1986, but Bradley’s take on the franchise would still need to await the 1987 publication of Wizardry IV and the departure of series creator Robert Woodhead.

Wizardry V marks the first entry in the series to be published on the Super Famicom/SNES (though a later remake of the first three Wizardry games would make its way to the Super Famicom in 1999). Its visuals would be enhanced, as had occurred with earlier series ports. A unique version of the SNES’ Wizardry V would even be broadcast on Nintendo’s short-lived Satellaview peripheral in 1997 and 1998. The Satellaview was noteworthy for broadcasting playable games at specific times using a satellite radio network prior to the advent of online digital distribution platforms, and its versions of other SNES software often featured unique elements that have subsequently been lost to time.

Wizardry VI: Bane of the Cosmic Forge (1990)

Andrew Greenberg departed Sir-Tech in 1988, leaving David W. Bradley as the primary actor guiding work on the Wizardry franchise. Development quickly began on Bane of the Cosmic Forge under Bradley. As neither of the original creators were still involved in the project, Wizardry VI would make a number of major updates to the long-running series.

The most immediately noticeable evolution is the game’s visual design. No longer bound to the aging Apple II platform, Wizardry VI released on Amiga and IBM PCs with full-color dungeons. Monsters had formerly been comprised of four colors, but could now be rendered in sixteen colors; this paled in comparison to some contemporary computer games producing 256-color images, but was a conspicuous upgrade on what Sir-Tech had previously offered to fans of its flagship franchise.

Aside from a branching story featuring player choices and three different endings, Wizardry VI adds several significant new character customization options. New races include Faerie, Lizardman, Dracon, Rawulf, Felpurr, and Mooks; most of these are animal-human hybrids, but the last is amusingly reminiscent of a Sasquatch. New classes include the Bard, Ranger and female-only Valkyrie.

That gender-oriented class distinction is indicative of a wider mechanic introduced to the series for the first time. A character’s gender, selected during the character creation sequence, has an impact on his or her stats and job opportunities. Males have a boost to strength while experiencing reduced personality and karma; the latter two attributes govern interpersonal relations with non-violent NPCs and luck, respectively. Females have reduced strength but increased personality and karma. Male characters can be Lords, while female characters can be Valkyries. All classes’ skills and access to schools of magic have been dramatically altered as well.

Not content to upend only the series’ visuals and underlying game mechanics, Bradley and his team also created a new level structure. Gone were the central dungeon and central town. Instead, players navigate a castle, forest and mountains. All saving and equipment gathering must be completed in the various locations the player characters find themselves. Wizardry VI is paradoxically the most and least dungeon-heavy entry in the series.

Those various locations are, in the original version, uniformly depicted with brick walls. Wizardry had come a long way in updating its visual presentation, but devising jungle and mountain areas as architecturally distinct seems to have been a bridge too far. Those who picked up ports of the game for Super Famicom or SEGA Saturn, on the other hand, would discover that the non-castle areas had finally integrated unique textures.

Wizardry VI would mark something of a new beginning for the series after the experimental Wizardry IV and Wizardry V. Woodhead and Greenberg were gone, giving Bradley free reign to drag the franchise out of its early 1980s aesthetic. Unlike the gaming landscape of 1981, numerous RPGs were available to consumers by the early 1990s. Sir-Tech could only hope that the series’ designer would be able to re-establish the dominance of their influential IP a decade after its debut.

Wizardry VII: Crusaders of the Dark Savant (1992)

His previous game having been well-received, David W. Bradley received support from Sir-Tech to branch out still further from Wizardry’s roots. Many mechanical systems remained in place, but Wizardry VII would largely abandon its Dungeons and Dragons aesthetic in favor of science fiction tropes. At the same time, continuity would be preserved through a revival of the character import feature.

The narrative reflects Wizardry VII’s status as the middle chapter of a new trilogy. Wizardry VI had ended upon a revelation that its central artifact – the titular Cosmic Forge – originated in space. The party then discovered a spaceship and set off for parts unknown. Depending upon certain decisions made in Wizardry VI, as well as the player’s decision about whether he or she imported a party from the preceding adventure, the party’s starting location in Wizardry VII can be one of four alternatives.

The plot of Wizardry VII begins in space, on-board a vessel in transit, but quickly leads to the surface of Planet Guardia. At this point, the player character’s party races to secure yet another artifact before another group of characters gets to it. The Astral Dominae is simultaneously sought by a variety of factions, each with their own motives. These factions each have a tracked statistic of affinity for the player character’s party. The player can improve or reduce this affinity through talking to or engaging in combat with members of each faction.

Faction members, along with monsters, are encountered across Planet Guardia’s numerous environments. These are navigated using an interface quite similar to Wizardry VI. Gameplay still proceeds from a first person perspective as the player characters navigate gridded areas one turn at a time. These turns take on greater urgency than earlier entries in the series, as members of competing factions actually take turns simultaneously and can gather the game’s various plot macguffins before the player does.

Environments are more diverse than any preceding series entry. The setting spans a vast overworld, though areas are cosmetically represented by only four tilesets. Player characters visit multiple towns and dungeons along their way, making greater use of navigation skills like swimming and climbing. Wizardry VII offers few signposts to guide the player between noteworthy locations, however. The only mitigation against becoming hopelessly lost is a new automap feature. Guardia is an open world in the truest sense, inspiring frustration and acclaim in equal measure.

Ports would again be produced throughout the 1990s; Wizardry Gold quickly became the most notorious of these re-releases upon its publication in 1996. Sir-Tech added voiced narration of varying quality and fully overhauled the visual design, upsetting many players who believed that the original graphics were superior. This port’s chief improvement was its compatibility with modern operating systems, fully supplanting the original DOS version’s marketplace dominance.

Wizardry 8 (2001)

The computer role-playing game (CRPG) sub-genre would evolve significantly during the 1990s. Wizardry had inspired the JRPG sub-genre overseas, but its Dungeons and Dragons-influenced approach to turn-based combat was dwindling in appeal back home. RPGs made in the West were increasingly focused on narrative, decision-making and real-time or hybrid real-time/turn-based combat mechanics. Wizardry VII had made gestures towards a greater emphasis on plot and decision-making with its faction diplomacy system, but this fell short of what other studios – especially Elder Scrolls creator Bethesda – would do with their complex, interlinked non-player characters. The absence of a new Wizardry release in the late 1990s seems to confirm that Sir-Tech’s approach to game design had grown less popular among game enthusiasts.

At the same time, several major changes behind-the-scenes would derail production on a new series entry. David W. Bradley left Sir-Tech in the midst of a lawsuit filed by Andrew Greenberg and Robert Woodhead over a dispute concerning series royalties; Bradley claims not to have been involved in the suit, but the challenging circumstances must have cast a pall over the Wizardry franchise. Sir-Tech’s United States division then went bankrupt in 1998. This studio had already announced the development of Wizardry 8, but responsibilities would pass to Sir-Tech Canada upon its collapse. Three more years would pass before fans had the opportunity to discover how their favorite series might adapt to a radically changed video game landscape.

This time would be spent working on an outsourced version of the game, as Australia’s DirectSoft handled it briefly before it was reassigned to Sir-Tech Canada staff. Linda Currie, who had co-founded Sir-Tech Canada and co-designed strategy RPG Jagged Alliance during the 1990s, would take on the role of producer for the new Wizardry project. Wizardry 8 designer Brenda Brathwaite was also a veteran of the Jagged Alliance series. These two individuals would be primarily responsible for re-establishing Wizardry in the 21st Century .

The game doubles down on the science fiction aesthetic of Wizardry VII. Rather than confining much of its technologically-oriented visual design to the introduction and flavor text however, Wizardry 8 instead has the in-game setting largely eschew fantasy tropes. The player character’s party explores a newly discovered planet in search of three mystical artifacts. One of these, the Astral Dominae, is held by a powerful cyborg named the Dark Savant (for whom the trilogy of games comprising Wizardry VI to 8 is named). The Dark Savant had taken the artifact during the conclusion of Wizardry VII, setting up a cliffhanger that would remain unresolved for almost a decade.

Wizardry VII’s multiple endings function as the jumping-off point for how the narrative begins in Wizardry 8. Though this informs a variety of details in the early game, much of the campaign is dedicated to exploring an overworld, towns and dungeons in a manner somewhat similar to its direct predecessor. The biggest difference is the integration of optional real-time combat and the elimination of gridded environments. The player character’s party, still represented only by character portraits as the player navigates from a first-person perspective, can roam the landscape free from turn-based movement and rigid ninety-degree turns.

Enemies, meanwhile, are no longer encountered randomly as the player wanders. They are instead depicted on the exploration screen and can be avoided or engaged at the player’s will. This is primarily an improvement, though it opens the possibility for combat to be interrupted by additional monsters wandering the surrounding area. The same occurs with friendly NPCs, leading to scenarios where NPCs can be inadvertently killed by hostile enemy characters.

The potential for elements of the game to be sealed off by poor quality assurance or quirky mechanics is not isolated to combat, unfortunately. Quest items can sometimes fail to appear when needed, leading players to either encounter a fail state or reload earlier save data. This would come to be a hallmark of the open-world RPG – similarly messy titles Ultima IX: Ascension and The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind would be released in 1999 and 2003, respectively – but remained surprising to players familiar with the comparatively less ambitious and more polished early Wizardry games.

The most striking series evolution encountered in Wizardry 8 might be cosmetic. For the first time, the world is rendered as a fully textured polygonal space. Monsters and NPCs are similarly drawn. Wizardry had finally, for perhaps the first time in its lengthy history, caught up with its competitors’ visual design.

Sadly, Wizardry 8 would also represent the franchise’s last hurrah. Its development staff was laid off months ahead of its release and Sir-Tech Canada would close in 2003. The series had inspired many imitators, and indeed would continue to do so overseas, but its core concepts had proven challenging to iterate upon without diluting its identity.

Spinoffs

The Wizardry series has had a staggering number of spinoffs over the past 37 years, and I’m afraid I’ll only be able to cover the highlights here. For more information, I strongly recommend Hardcore Gaming 101’s coverage of Wizardry. That was an important source for this article more generally, but Sam Derboo’s exhaustive overview is particularly helpful for identifying the long and complicated history of series spinoffs.

Sir-Tech’s first major offshoot from the core series was released for PCs and the SEGA Saturn in 1996. Nemesis: The Wizardry Adventure was Wizardry 8 producer Linda Currie’s inauspicious first role in the franchise’s development. She had already produced the successful Jagged Alliance (1995), but spinning off of Wizardry would still prove challenging.

Nemesis is highly reminiscent of point and click adventure games from the 1990s, especially Myst. It retains certain cosmetic elements of the Wizardry franchise – a first person point of view and semi-gridded navigation chief among them – but otherwise abandons the series’ identity entirely. The player takes on the role of a defined player character as he explores pre-rendered environments, battles monsters in real-time, and solves rudimentary puzzles. Lacking most of the features that had brought fans to the franchise, the undistinguished Nemesis was a critical disappointment.

During the 1990s in Japan, on the other hand, several local developers had created their own takes on the venerable Western RPG franchise. Most of these were never exported in spite of being rather intriguing; among these semi-official Wizardry titles are Starfish’s portable Wizardry Empire (1998) and Michaelsoft’s highly anime-influenced futuristic dungeon crawler Wizardry Xth (2005). Happily, Atlus localized one of these games for an international release in 2001.

Wizardry: Tale of the Forsaken Land (2001) represents one of the only Japan-developed series entries to be published in North America. Developed by Racjin, this PlayStation 2 game has more in common with the series’ roots than the contemporary Wizardry 8. Players create a single player character who has access to a town and a dungeon at the game’s outset. NPCs join the party and accompany the player character on his or her quest to explore the dungeon. Play involves menu navigation while in town and turn-based first-person navigation of a gridded landscape when underground. Progress can only be saved in town, though Racjin integrated a modern convenience in the form of suspend points; these may be generated anywhere in the dungeon, allowing the player to turn off his or her console but automatically self-deleting when the adventure is resumed. The game would enjoy praise by some outlets as a nostalgic return to the franchise’s earliest days while being simultaneously criticized by others as hopelessly outdated. Its few concessions to modern game design, including fully 3D graphics, were not enough to impress young audiences and no further entries in the sub-series were published outside of Japan.

Wizardry Online (2011), a free-to-play massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) adaptation of the series, was released a decade after its last numbered entry. This was part of a broader attempt to revitalize the series for the 2010s, but would be widely panned at the time of its international release. Players create a character and explore dungeons, but that is the extent of the game’s similarities to its parent series. The player character is controlled from a third-person perspective, all combat occurs in real-time, and a party can consist only of multiple human-controlled avatars cooperating with one another. Progress to new areas is often gated behind steep time or real-world money investments, echoing a poor design choice of so many other free-to-play titles. With little to draw players to it, Wizardry Online was shut down in the West by the end of 2014.

Conclusion

Wizardry is rightly regarded as one of the most significant video game series in the medium’s half-century history. Pulling generously from Dungeons and Dragons, along with a variety of niche dungeon crawlers popular among university students in the late 1970s, Robert Woodhead and Andrew Greenberg established the template for the following fifteen years of Japanese role-playing games. This sub-genre would eventually come to define itself through a variety of distinct tropes, but its foundational entries (including Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, and Shin Megami Tensei) were all directly inspired by Wizardry. The series’ star would diminish in the 1990s, even as its ambitions expanded, collapsing amongst the financial difficulties of its publisher by the early 2000s. Still, Wizardry occupies a unique place in the pantheon of noteworthy video games and its influence will likely be felt for decades to come.

You must be logged in to post a comment.