Part Three in a series; see parts one and two.

Robert Stripling was concerned. HUAC’s chief investigator didn’t trust Whittaker Chambers, their star witness in the case against Alger Hiss, feeling that even now he’d withheld some crucial evidence, for reasons known only to himself. “He sits and lights his pipe, he is cold and calculating, and he knows exactly what he will do three weeks hence,” Stripling complained. Since their case rested entirely on Chambers’ word, it unnerved him. For now, he and other committee members swallowed their reservations as the Case became an unparalleled public spectacle.

It had been eight days since Hiss and Chambers met face-to-face in executive session. In preparation for the public showdown, the Committee called a number of witnesses trying to corroborate details of the two’s relationship. Among them was Priscilla Hiss, who dimly remembered George Crosley – Chambers’ alleged alias – as “a small person, very smiling person—a little too smiley, perhaps.” Others Chambers named in his initial testimony, including John Abt and Lee Pressman, denied knowing Chambers at all, nor did peripheral witnesses clarify details about Hiss selling Chambers a 1929 Ford or his leasing Chambers an apartment. It seemed like the case, whatever its merits, would come down to public drama.

Already theatrical, Hiss and Chambers’ dispute exploded into soap opera on August 25th. Thousands of sweating spectators and jostling journalists packed the Capitol; television crews broadcast the hearings live to millions across the country, the first glimpse many Americans received of Congress in action. Those who knew the two men only from newspaper accounts and newsreel footage could now judge for themselves. J. Parnell Thomas, the Committee chairman, summarized the stakes: “As a result of this hearing, certainly one of these witnesses will be tried for perjury.”

Hiss went first. And before the television cameras, the cool, collected Ivy Leaguer lost his composure, along with the Establishment credibility he’d accrued over the past three weeks. All that remained, it seemed, was outrage. He insisted that “the important charges are not questions of leases, but questions of whether I was a Communist.” He claimed that Chambers, “a self-confessed liar, spy and traitor” was inherently untrustworthy, denying both the broad strokes and details of his accusations. He also cited a witness confirming that Chambers used the alias George Crosley. This was Samuel Roth, a publisher of erotic literature who’d printed several poems by Chambers in the ’20s. This, however, was the only point Hiss scored in the entire hearing.

Richard Nixon wouldn’t let him escape. “The issue in this hearing today is whether or not Mr. Hiss or Mr. Chambers has committed perjury before this committee, as well as whether Mr. Hiss is a Communist,” the Californian replied, outlining the evidence of the leases and car sales supporting Chambers’ testimony. Stripling produced a photostatic record proving that Hiss owned the property where Chambers resided. Hiss conceded that the document’s signature “also looks not unlike my own handwriting,” and claimed Stripling had withheld the documents from him. Stripling responded that the car dealer still possessed the original; he merely procured a copy.

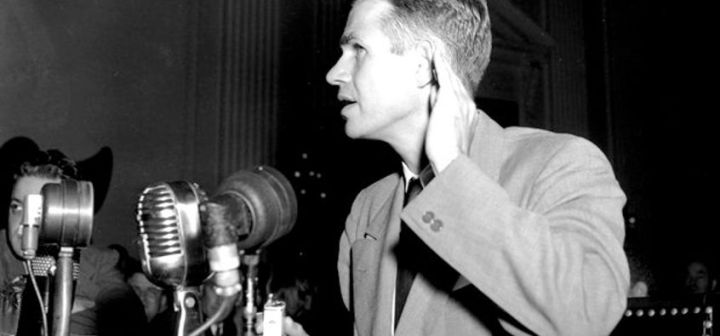

To viewers at home, Nixon and Stripling’s questions might have seemed arcane, even unfair. Hiss could be forgiven for not remembering trivial details years later. But Hiss’s combativeness undercut him. He sparred over these obscure points, avoiding lifelines that might have shored his credibility. He seemed bored, angry or agitated, straining or resting his head in his hands (caused in part by Hiss suffering from partial hearing loss). He repeatedly questioned Chambers’ state of mind, demanding to know “whether he has ever been treated for a mental illness.” Both in words and presentation, Hiss didn’t resemble an innocent man.

When Whittaker Chambers appeared, his flair for melodrama proved more compelling than Hiss’s evasions. He reiterated the evidence from previous trials and denied Hiss’s curious claim that Chambers had engaged in espionage (something Chambers hadn’t even suggested). Admitting “I am not a saint,” he characterized Hiss as “a devoted and…rather romantic Communist” who had been Chambers’ “closest friend…in the Communist Party.” He related that, after deciding to leave the Party, he urged Hiss to join him; Hiss declined. (In his memoirs, Chambers claimed that Alger Hiss was silent, while Priscilla Hiss dismissed his qualms as “mental masturbation.”)

After finishing his testimony, Chambers rumbled out a typically verbose, self-justifying soliloquy. “I do not hate Mr. Hiss,” he asserted. “We were close friends, but we are caught in a tragedy of history. Mr. Hiss represents the concealed enemy against which we are all fighting, and I am fighting. I have testified against him with remorse and pity, but in a moment of history in which this Nation now stands, so help me God, I could not do otherwise.”

The hearing lasted ten tense, dramatic hours. On a superficial level, it appeared that Chambers had won the day, seeming resolute where Hiss was testy and defensive. A young spectator rushed up to Chambers and shook his hand; Hiss was cossetted by his friends and family. “Either you or Mr. Chambers [is] the damnedest liar that ever came on the American scene,” F. Edward Hebert told Hiss before the hearing concluded. But the Committee washed its hands of further involvement; resolving the Case lay in its protagonists’ hands.

In their August 17th meeting, Hiss challenged Chambers to repeat his charges in a public forum. On August 27th, Chambers obliged him. He appeared on the radio program Meet the Press, where a panel of journalists grilled him. “Alger Hiss was a Communist and may be now,” Chambers told Edward Folliard of the Washington Post. Though the journalists peppered Chambers with tough questions about his testimony, Chambers held firm. “I do not think Mr. Hiss will sue me for slander or libel,” he assured his questioners, throwing down a gauntlet to his rival.

Hiss responded the following day with a vicious, innuendo-laden open letter. He called Chambers mentally ill, “a confessed traitor” who wallowed “in the sewers for the past thirteen years, plotting against his native land,” calling him “somewhat queer” in the bargain. He didn’t mention a lawsuit, however; Chambers testified in the trial of J. Peters, his former handler, while Nixon and other Committee members focused on the fall elections. For a month, it seemed possible that “the Case” would finally vanish from public consciousness.

Until September 27th, when Hiss finally filed slander charges against the “untrue, false and defamatory” claims made by Chambers. Chambers responded by “welcoming” his suit and warning of “the audacity or the ferocity of the forces which work through him.” Now the courts would have to decide as the Presidential election reached its climax.

Harry Truman ignored Congressman Sam Rayburn’s warning that “there is political dynamite in this Communist investigation,” and kept defending Hiss. He attacked HUAC for “injur[ing] the reputations of innocent men” and called the Republican Party “the unwitting ally of the Communists in the country.” Truman, in the midst of his long shot reelection campaign, was in a combative mood; Republicans had rendered Hiss’s guilt or innocence into a partisan issue, much as they’d made Red-hunting a major factor in their midterm elections two years earlier.

Labeling Truman a Communist sympathizer was patently ridiculous. In 1941, while Senator, he’d reacted to Hitler’s invasion of Russia by advising, “if we see that Germany is winning we ought to help Russia and if Russia is winning we ought to help Germany, and that way let them kill as many as possible.” As President, his Truman Doctrine asserted America’s will to resist Soviet expansion (the Berlin Airlift served as an international backdrop to the campaign). Domestically, he’d cracked down on railroad strikers, instituted loyalty oaths for Federal employees and fired pro-Soviet Henry Wallace from his cabinet (causing Wallace to run a quixotic presidential campaign).

Thomas Dewey, making his second run at the Presidency, obliged him (and frustrated his fellow Republicans) by minimizing the issue. The New York Governor proved commendably fair-minded on the issue, focusing on Truman’s perceived corruption and incompetence while soft-peddling Red-baiting. During the 1948 primaries he debated Harold Stassen over proposed legislation to outlaw the Communist Party, lecturing the Minnesotan that “there’s no such thing as a constitutional right to destroy all constitutional rights.” In any case, Henry Wallace’s campaign attracted so many actual Communists that it proved difficult to make charges against Truman stick.

On November 4th, two days after Truman’s surprise victory over Dewey, preliminary hearings in Hiss’s slander suit began in Baltimore. During the course of his testimony, Chambers dropped a bombshell: that during Hiss’s time in the State Department, he “occasionally gave the Communist Party bits of information which might be useful to them.” Richard Cleveland, Chambers’ attorney, was as shocked as anyone else; he requested a recess and huddled with his client, demanding an explanation.

Puckishly, Chambers addressed Cleveland: “You feel, don’t you, that there is something missing?” Receiving an affirmative answer, he told the attorney that “I am shielding Hiss.” He affirmed something that Hiss imprudently hinted at before HUAC, and Chambers hadn’t let anyone (not Nixon, Stripling or the Committee, not the press, not his own attorney) know: that he and Hiss, not only had they been Communists, but they worked as spies for the Soviet GRU.

Chambers’ reticence in providing this information baffled contemporaries and historians alike, leading to accusations of dishonesty, fraud or coaching by investigators. Biographer Sam Tanenhaus suggests that Chambers was playing a cagey game, not to trick investigators but to avoid implicating his friend. “Those he had hoped to satisfy with generalities about Communist infiltration had instantly detected suspicious lacunae in his story,” Tanenhaus argues. “Hiss, whom Chambers had been trying to protect, had misread the signals altogether, concluding…that he lacked substantiating evidence.”

It’s also possible that Chambers, he of the dread pronouncements about a battle between Christian civilization and Communist barbarism, deliberately chose the most shocking moment to spring this information on investigators. Or a simpler explanation still, suggested by John A. Farrell, that “to expose Hiss’s espionage, he would have to expose his own.” Certainly now, with his hand forced, Chambers proceeded with due theatricality.

On November 14th, Chambers retrieved an envelope of documents from Nathan Levine, his wife’s nephew; Chambers had concealed it in an old dumbwaiter in Levine’s Brooklyn apartment. Inside was a small but potentially incriminating collection of documents: legal paper both handwritten and typed, two developed roles of microfilm and several undeveloped canisters. He presented the documents to Cleveland, who urged Chambers to present them into evidence two days later.

Chambers insisted, “I was particularly anxious…because Mr. Hiss is one of the most brilliant young men in the country, not to do injury more than necessary to Mr. Hiss.” His honeyed words didn’t matter. Hiss’s lawyers examined the materials, which were indeed damning. The documents were transcripts of diplomatic cables and State Department memoranda; William Marbury, Hiss’s lead attorney, was stunned that “I recognized what seemed to be Alger’s handwriting” on one of the papers. If authentic, the information would blow “the Case” back into the public headlines.

It was Bert Andrews, Richard Nixon’s journalist ally, who set things in motion. “I think Chambers produced something at the Baltimore hearing,” he told the Congressman. “He may have another ace in the hole.” The news couldn’t have come at a better time for HUAC – Truman and other Democrats, emboldened by the President’s reelection, were calling for the Committee’s abolition – but not for Nixon, who was preparing to leave for a vacation with his wife.

“I’m so goddamn sick and tired of this case,” Nixon told Robert Stripling. “I don’t want to hear any more about it and I’m going to Panama.” Stripling, however, was insistent, and together they visited Chambers on his farm in Westminster, impatiently watching Chambers milk his cows before delivering a noncommittal response. “I don’t think he’s got a thing,” Nixon fumed to Stripling, before leaving on his cruise with Pat.

A few days later, Chambers contacted Stripling, indicating he was ready to turn over his evidence. Stripling wasn’t available, so his assistants Donald Appell and William Wheeler drove to Chambers’ home in the dead of night. Tromping around in the dark, Chambers led them to a pumpkin patch and produced a hallowed-out gourd featuring the microfilm. “What is this, Dick Tracy?” Wheeler asked Appell, flabbergasted by their informant’s latest coup.

When Stripling examined the microfilm, he found several copies of State Department cables – the originals, he suspected, of the transcripts Chambers had earlier presented. Not all of the film was damning, or even useful. One roll was completely blank; another appeared to be a mundane Navy document about fire safety. If the evidence wasn’t completely new, it was certainly dramatic; John Rankin, the only HUAC member then in Washington, heightened the drama by placing the microfilm under twenty-four hour guard.

Richard Nixon, chagrined at having to abort his vacation, flew back to America from the Bahamas on a Coast Guard plane (leaving Pat behind to return home, alone, several days later). He initially thought the “pumpkin papers” were a joke; informed of Chambers’ theatrics, he wondered “if we might really have a crazy man on our hands.” Nonetheless, Nixon didn’t hesitate to take advantage of the situation. As he and Robert Stripling posed with the microfilm for photographers, one reporter asked Nixon if they knew the film’s date of manufacture. Neither he nor Stripling had an answer.

Stripling sent the film to Eastman Kodak’s local office for analysis. Their initial conclusion was that the film hadn’t been manufactured until 1945…years after Chambers accessed these documents. An enraged Nixon called Chambers and confronted him with the information.

“It cannot be true,” Chambers insisted, “but I cannot explain it. God must be against me.”

“You better have a better answer than that!” Nixon raged, demanding that Chambers provide a face-to-face explanation. He’d spent months working with Chambers, tolerating his Delphic obscurities, his pompous pronouncements and evasions; he recognized that he’d staked his political career on Hiss’s guilt. Now he was fully prepared to eat crow and admit his mistake; but first, he planned to give Chambers a piece of his mind.

Just before Nixon and Stripling departed their office, Kodak’s representative called back. Turns out they’d made a mistake; the brand of film had, in fact, been manufactured in 1938, then discontinued during World War II and revived in 1945…accounting for the mix-up. The two men stared incredulously at each other for a moment, then Stripling whooped with joy, grabbing a nonplussed Nixon and waltzing him around the office.

Chambers didn’t see the humor. He resigned from Time, convinced that his career was over; he bought several tins of rat poison, struggling to hide his melancholy during a grand jury appearance in New York. Even Alger Hiss, watchining Chambers’ testimony, sympathized with his nemesis. “He looked dejected and slipped unobtrusively through the stairway door,” Hiss recalled, avoiding reporters and well-wishers as he left. Whatever satisfaction Chambers had destroyed his career, and a man he’d considered a friend; the mix-up with the film seemed like a cosmic judgment he couldn’t avoid.

Ongoing personal attacks took their toll, as well. By now, Chambers’s sexual proclivities and battles with mental illness became fair play for press comment and ridicule: a slur circulated in liberal circles that Chambers was romantically entranced by Hiss, who spurned his attentions. Another rumor claimed that Chambers and his wife engaged in wife-swapping with other, ex-Communist couples. Even Robert Stripling, his earlier suspicions confirmed, complained that Chambers had “misled the investigators” by withhold the crucial documents, and suggested indicting him for perjury along with Hiss.

Cruelest of all was psychiatrist Carl Binger, whom Hiss hired to craft a profile of Chambers. Having never met Chambers, Binger nonetheless diagnosed him as a psychopath based purely on Chambers’ writings and public statements. He harped on Chambers’ translation of Franz Werfel’s novel Class Reunion, about a well-to-do-teenager ruined by a jealous friend, as if the book were Chambers’ own work. Historian Allen Weinstein notes that Chambers also translated Bambi, which hardly showed “that the translator was a gun-shy deer.”

On December 10th, Chambers (staying at his mother’s house) wrote several suicide notes which left in the attic. He then tried to asphyxiate himself with fumes from the rat poison. Chambers lost consciousness; he woke up in a puddle of vomit the next morning. His mother berated him, telling Chambers that “The world hates a quitter!” For his part, Chambers felt ashamed that he’d failed; he couldn’t escape the Case, even through death. It would be six more agonizing months before he finally received vindication.

In June 1949, the grand jury indicted Hiss for perjury (the statute of limitations on espionage having expired). The first trial resulted in a hung jury; a second trial saw yet another twist. The FBI located a Woodstock typewriter which matched the microfilmed files. This proved decisive evidence in a second trial, which resulted in Hiss’s conviction on January 25, 1950. Speculating darkly about the prosecution’s “forgery by typewriter,” Hiss went to Lewisburg Penitentiary for a five year prison sentence.

Despite a few rearguard defenses by Hiss’s friends (“I will not turn my back on Alger Hiss,” proclaimed Dean Acheson, Truman’s Secretary of State) most Democrats seemed happy the Case had ended. Chambers, too, shunned the limelight, working as a freelance writer before becoming an editor for National Review. His portentous memoir, Witness, became a best-seller and cemented him as an idol of the anticommunist right, even as Chambers warned about Joe McCarthy’s recklessness and savaged Ayn Rand. He died in 1961, having achieved some degree of vindication, if not happiness.

Hiss served his prison sentence without incident, rubbing shoulders alongside fellow ex-Communists William Remington and David Greenglass, and several organized crime figures; on one occasion he met Frank Costello, commiserating with the New York godfather over their mutual experiences before Congress. Through several memoirs and friendly media coverage, Hiss rehabilitated his reputation; as early as 1962, he appeared on ABC’s “Political Obituary” for Richard Nixon after he lost California’s gubernatorial race. His innocence became sacrosanct for the Cold War left, any suggestion of his guilt heretical – not least after Nixon’s presidency and fall from grace.

Hiss pursued his vindication with a disturbing single-mindedness. “By entering into a campaign for vindication,” G. Edward White writes, “Hiss signaled to his closest friends that there would be no getting beyond his central mission in life.” Hiram Haydn, an editor at Random House, remarked on Hiss’s ability to shift his arguments, even his personality, chameleon-like as the situation dictated. “Mask succeeded mask, role role, personality personality,” he marveled, noting that in conversation, Hiss “answer[ed] my questions with the manner of a shrewd, precocious boy who was playing games and admiring his skill at them.”

Yet for decades, many accepted Hiss at face value while denouncing his critics as accessories to Nixon-McCarthy Red-baiting. When Allen Weinstein’s book Perjury appeared in 1978, arguing Hiss’s guilt, various left-wing publications attacked. Most strenuous was Victor Navasky of The Nation, who denounced Weinstein as “an embattled partisan, hopelessly mired in the perspective of one side.” The most significant error Navasky uncovered was Weinstein wrongly identifying one interview subject, union leader Samuel Krieger, as a murderer. Krieger sued Weinstein, who paid $17,500 and publicly apologized. Egregious as this mistake was (certainly for Krieger!), White argues, neither it nor other errors “were central to [Weinstein’s] arguments about Hiss’s guilt.”

Only in the 1990s, shortly before Hiss’s death in 1996, did the picture become clear. Dmitri A. Volkogonov, a former KGB official, proclaimed Hiss’s innocence in 1992, then quickly recanted. Declassified NSA files (the VENONA Project) listed Hiss as a GRU agent named ALES, whose profile (a high-ranking diplomat who passed State Department documents to the GRU and accompanied Roosevelt to Yalta) matches Hiss. Other documents from Russian and Hungarian archives further condemned Hiss. While a handful of writers – Victor Navasky of the Nation, historian Kai Bird and novelist Joan Brady – maintain a rearguard action in Hiss’s defense, for most the Case is finally settled.

Of course, many left-leaning writers are as susceptible as conservatives to binary thinking. One can accept Alger Hiss’s guilt and that the public reaction his investigation triggered, snowballing into a decade of anticommunist hysteria, proved deeply harmful. Whittaker Chambers and Elizabeth Bentley, however flawed or exaggerated their testimony, could verify most of their charges. Later informants, and certainly the investigators who enabled them, were less reliable – and much more dangerous.

Sources and Further Reading

This article draws upon: Whittaker Chambers, Witness (1952); Alistair Cooke, A Generation on Trial: U.S.A. v. Alger Hiss (1950); John A. Farrell, Richard Nixon: The Life (2017); Ted Morgan, Reds: McCarthyism in Twentieth Century America (2003); Sam Tanenhaus, Whittaker Chambers: A Biography (1997); Allen Weinstein, Perjury: The Hiss-Chambers Case (2013 revised edition; originally published 1978); and G. Edward White, Alger Hiss’s Looking-Glass Wars: The Covert Life of a Soviet Spy (2004).

You must be logged in to post a comment.