In 1850, the United States of America stood on the edge of a precipice. The Mexican War added 529,000 square miles to the United States, re-sparking long dormant debates about the future of slavery. Southern slave owners had long maintained disproportionate government power by assuring that.

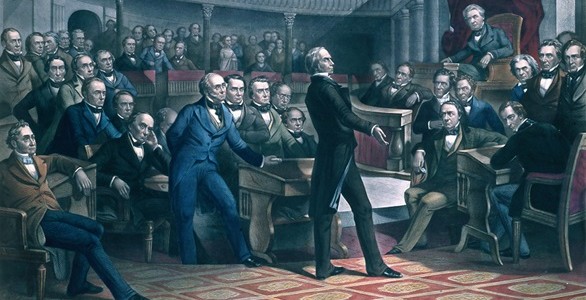

The result was the Compromise of 1850, one last, titanic effort by America’s second generation of statesmen to avert civil war. Henry Clay, Daniel Webster and John Calhoun (wheeled into Congress on his deathbed), the three titans of their age, quarreled and argued over how to preserve the peace without giving offense to any part. Among other terms, California entered the Union as a free state, the newly acquired territories would decide for themselves whether, and most momentously of all, a Fugitive Slave Law was enacted to ensure return of escaped slaves to the South.

For most American politicians and middle class whites, this seemed a reasonable, even noble endeavor to maintain the status quo. For blacks and their abolitionist allies, of course, it merely demonstrated how little black lives mattered. Their instant response was violent defiance. Martin Delaney, a black physician and orator from Pittsburgh, vowed that “if any man approaches that house in search of a slave…and I do not lay him a lifeless corpse at my feet, I hope the grave may refuse my body a resting place.” John Brown, heretofore an obscure New England merchant of evangelical inclinations, told Frederick Douglass that “slavery was a state of war, and the slave had a right to anything necessary to his freedom.”

Not that they needed much incentive to fight back. Ever since the Continental Congress, American statesmen had papered over the issue of slavery, and its inherent fault lines, with compromises and concessions, mostly favoring the status quo at best and openly endorsing Southern slaveholders at worst. Even Northern blacks faced limitations on voting, property holding and basic legal rights, along with resentment and occasional violence from their white neighbors.

Such resentments took various forms. Blacks were hired only for manual labor and unskilled itinerant jobs; successful black men became suspicious, while anyone vaguely criminal found themselves imprisoned. (Nearly a third of Pennsylvania’s prisoners in 1850 were black, compared with three percent of the state’s population.) More perniciously, freed blacks invariably suffered social snubs, segregation and media caricatures as ineducable outcasts and childlike imbeciles. Newspapers regularly ran sensational stories about black criminals, especially rapists, which Northern whites devoured with horrified glee. (The perils of miscegenation were something virtually all whites, North and South, agreed upon.)

Others resented blacks for taking jobs from white laborers. Irishmen in the North in particular detested freedmen as competitors, resulting in violence between the two groups. One newspaper worried that “poor whites may gradually sink into the degraded condition of the Negroes”; another correspondent, writing in 1860, wondered why abolitionists weren’t outraged over the death of white factory workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts. These reverse racists could not “forget [their] partialities and bear with the afflicted, whose only fault…is their white complexion.”

How could it be otherwise, one Pennsylvania newspaper argued, when “Africans, in their own country, left to their own unaided exertions, have not…made one single step in intelligence, industry or enterprise”? Such racist excretions certainly weren’t the result of cool-headed assessments of African history, the achievements of Egypt and Phoenicia and the Mali Empire weighed against the more recently emergent Western Civilization. Unable to weigh the impact of centuries of oppression, white Americans simply assumed that slavery, stupidity and sloth was the black man’s natural state.

If Northerners were indifferent to slaves and hostile to freedmen, Southerners were both murderous and creative in their racism. While Thomas Jefferson couched slavery as a grim necessity, later generations of Southern nationalists embraced it as divinely ordained and culturally necessary. Thus John Calhoun could claim “that the present state of civilization, where two races of different origin, and distinguished by color, and other physical differences, as well as intellectual, are brought together, the relation now existing in the slave holding states between the two, is, instead of an evil, a good. A positive good.”

Calhoun’s apologia clashed with reality, accounting for neither the masters’ regular brutality, nor various forms of slave resistance, from murder to suicide. It didn’t account for the periodic conspiracies and uprisings, of which Nat Turner’s in Virginia was the bloodiest and most traumatic. And it certainly didn’t account for the hundreds of slaves who annually fled North along the Underground Railroad, seeking asylum in free states or Canada, assisted by black freedmen and white abolitionists who risked their own lives and, in the former’s case, capture and repatriation into slavery themselves.

Southerners couldn’t square their self-image as benevolent masters with such defiance. Why would Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave who became America’s most famous black abolitionist, conclude that if Southerners “give [slaves] a bad master, and he aspires to a good master; give him a good master, and he aspires to freedom“? How could Harriet Tubman, who went on slave rescue missions carrying a brace of pistols, affirm that “I had a right to, liberty or death; if I could not have one, I would have the other”? How could innumerable other slaves risk dismemberment or death for a fleeting chance at freedom?

Since blacks were deemed too ignorant to act on their own, the logical culprits were Northern abolitionists. Abolitionist writings were outlawed throughout the South, while antislavery advocates risked imprisonment or death just for speaking. William Lloyd Garrison, the fiery Boston abolitionist, was so loathed that mobs nearly murdered him on several occasions (Elijah Lovejoy, an Illinois abolitionist, was murdered by pro-slavery Missourians in 1837). The fault lie not “in poor, deluded and frenzied blacks but…reckless agitators who counsel and applaud opposition to the established laws of the land.”

Or perhaps blacks were simply deranged. This was the thesis advanced by Dr. Samuel Cartwright, a Louisiana physician who postulated an illness called drapetomania to explain the inexplicable urge of slaves to escape bondage. “The cause in most cases that induces the Negro to run away from service is as much a disease of the mind as any other species of mental alienation,” Cartwright wrote, “and much more curable as a general rule.” Fortunately, this strange disease had an easy cure: Cartwright prescribed amputating slaves’ big toes, or else “whipping the devil out of them” to soothe their wayward condition.

Even more demented, it seemed, were those who fought back. In 1837, William Dixon, an escapee from Maryland, ran afoul of slave catchers in New York City. A mob of free blacks made a failed attempt to rescue him; Dixon spent two years in court fighting for his freedom afterwards. Even those sympathetic to Dixon deplored the recklessness of his rescuers. Samuel Cornish, a black Presbyterian minister and anti-slavery advocate, admonished New York blacks for taking the law into their own hands. By resisting recapture, Cornish wrote, “you…degrade yourselves, and all others in the least connected with you.”

At least Dixon, despite his difficulties, could rely on state courts to fight recapture. This wasn’t always the case; gangs of professional slave catchers prowled border states and northern cities alike, kidnapping escaped slaves and free-born blacks indiscriminately, then selling them into bondage. Solomon Northup, author of Twelve Years a Slave, became the most famous victim, but he was hardly alone; thousands of blacks found themselves sent south in this inhuman trade before the Civil War. Freedom’s Journal, an antislavery publication in New York, complained about “acts of kidnapping, not less cruel than those committed on the Coast of Africa,” but little could be done unless, like Northup, a victim was well-connected and extremely lucky.

Eric Foner writes that “the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 embodied the most robust expansion of federal authority over the states, and over individual Americans, of the antebellum era.” It offered freed slaves no redress or legal rights, nor did it allow Northern states the right to challenge recapture and rendition. Southerners who touted “states rights” as their mantra openly boasted that they would now bring the cocky Yankees to heel. Now, even slave owners who lost their property before the Law’s passage eagerly sought to exploit it.

Edward Gorsuch, a corn and wheat farmer living in Baltimore County, Maryland, was one such Southron. By all accounts Gorsuch was a benign slave owner, who neither beat nor mistreated his slaves, and provisioned for them to be manumitted at age 28. Nonetheless, four of his slaves – Noah Buley, Nelson Ford, and brothers George and Joshua Hammond – felt freedom more desirable. Helped by a freedman named Abraham Johnson, they climbed out a skylight in Gorsuch’s farm and snuck off in the dead of night. They walked north along the York Road until they reached Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where local Quakers sheltered them. They found work as laborers and farmhands and blended into Lancaster’s small but active black community.

Two years passed, with Gorsuch’s efforts to locate and recover his “property” fruitless, not least due to the hostility of Pennsylvania authorities. Finally, in August 1851 he received a tip from William Padgett, a Lancaster County resident allied with the slave-catching Gap Gang, that he’d spotted the escaped slaves in the nearby village of Christiana. With the fugitives located, Gorsuch, his son Dickinson, cousin Joshua, nephew Dr. Thomas Pearce and Deputy Marshal Henry Kline traveled to Philadelphia, received a formal warrant for the missing slaves; along with two Philadelphia policemen, they sought redress.

Though Pennsylvania abolished slavery in 1780, it only came under the aegis of compensated manumission, applying only to those born after that date; the last Pennsylvania slaves weren’t formally freed until the 1840s. Even among the Quakers, who abhorred slavery, abolitionist sentiments were often muted by racism and snobbery. An English Quaker lamented that Pennsylvanians were “kind to the colored people…but they still seem to consider them as…a people who have no right to a possession in the land that gave them birth.”

Nonetheless, by 1851 eastern Pennsylvania, and Lancaster in particular, hosted Quakers vehemently opposed to slavery, who counseled their members to harbor or assist fugitive slaves. It also hosted William Parker, a remarkable black abolitionist who responded to the Fugitive Slave Law with violent, angry resistance.

Parker had already lived a remarkable life, as incident-filled as more famous activists like Douglass (whom he’d known since their time together in bondage) and Tubman. Born in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, he endured the typical life of a southern field hand until age 16, when he fled after quarreling with his master. Parker arrived in Lancaster, Pennsylvania and settled in the small village of Christiana, becoming the unofficial leader of the county’s black population.

Just 29 years old in 1851, Parker inspired respect among both friends and foes. One white acquaintance dubbed him “bold as a lion, the kindest of men and the most steadfast of friends” – and, needless to say, deadliest of enemies. A deeply religious man, he quoted Scripture with the vehemence of a Baptist preacher and openly defied Federal laws he considered unjust. “My rights at the fireplace were won by my child’s fist,” Parker boasted; “my rights as a freeman were, under God, secured by own right arm.”

Organizing a local collective of Lancaster freedmen, Parker worked to shelter escaped slaves from the Gap Gang and other slave-stealing ruffians. Several years before Christiana, the Gap Gang kidnapped an escape slave named William Dorsey in Lancaster. Attempting to return Dorsey to Maryland, these slave catchers ran afoul of Parker and his men, who ambushed the slavers, killed two of them and secured Dorsey’s release. Perhaps if Edward Gorsuch knew this, he’d have been more reticent about pressing the issue.

After several days of travel, Kline, Gorsuch and their posse approached Parker’s property, a two-story stone farmhouse, on September 11, 1851. Having been forewarned by a local freedman, Parker and his partners (his wife Eliza, sister Hannah and brother-in-law Alexander Pinckney, two of the escaped slaves, whom Parker called Samuel Thompson and Joshua Kite in his account, and freedman Abraham Johnson) armed themselves and prepared for battle. Deputy Marshal Kline and Edward Gorsuch approached the house, with their men taking shooting positions in the field outside.

The conversation immediately struck a belligerent note. When Kline proclaimed himself a US Marshal, Parker retorted that he had no use for the United States or its laws and threatened to break Kline’s neck if he entered the house. Nonplussed, Kline stepped forward and challenged Parker. “I have heard many a negro talk as big as you,” he snarled, “and then have taken him; and I’ll take you.”

Parker glowered and responded: “You have not taken me yet.”

The argument continued for several minutes. Parker and Edward Gorsuch traded insults and Bible verses; Kline, befuddled by Parker’s defiance, explained the Fugitive Slave Law to Parker, who brushed off his lecture as immaterial. When Kline threatened to burn down Parker’s home, Parker called him a coward and said he wouldn’t dare. Similarly, the band didn’t fall for Kline’s claim that he was summoning reinforcements from Lancaster. Eliza Parker further contributed to the tension, brandishing a corn knife and threatening to decapitate the trespassers.

The blacks also seemed to relish insulting their tormentors. As Gorsuch and Parker swapped Bible verses, Parker’s colleagues started singing an African spiritual (“preaching a sinner’s funeral sermon,” one announced). Abraham Johnson appeared and mocked Gorsuch, asking him “does such a shriveled up old slaveholder as you own such a nice, genteel young man as I am?” This insult drove Gorsuch to an outburst of profanity and further threats, though his colleagues grew unnerved by the freedmen’s continued defiance.

At this point, Kline and Gorsuch lost patience and tried forcing their entry. Immediately, Eliza blew a horn to summon assistance from local blacks. One of Parker’s men struck Gorsuch on the head with a staff, forcing him and Kline to retreat from the house. As they did, the Marshal spotted one of the freedmen stationed in the upper story, aiming at him with a rifle. Kline fired a shot and missed, prompting a shot in return, which also failed to hit its target. A brief exchange of gunfire resulted in no casualties, though Joshua Gorsuch was struck by a piece of wood thrown from the windows, and the posse withdrew out of firing range.

During this uneasy truce, the frustrated lawmen intercepted Castner Hanway, a Quaker miller who arrived unarmed and hoped to negotiate a peace between the two sides. He tried to persuade Gorsuch that Parker’s men would fight to the death; Gorsuch responded melodramatically, “My property I will have, or I’ll breakfast in hell.” Even an appeal from his son Dickinson, who feared that black reinforcements summoned by Eliza would make arrest impossible, didn’t phase him. “It would not do to give it up that way,” Gorsuch snarled. Now it was a question of honor.

Before Gorsuch could exact satisfaction, the posse watched as a group of freedmen (probably around 20 to 25 total) arrived to save Parker. They had been summoned by Eliza’s horn and a white Quaker, Joseph Scarlett, who rode through Christiana warning blacks that kidnappers were coming. Parker’s rescuers carried any weapons they had, from rifles to scythes, clubs and the ubiquitous corn knives. Even now, Gorsuch didn’t give in. Samuel Thompson grew bold enough to emerge from Parker’s house and taunt the slave catchers: “Old man, you had better go home to Maryland.” “You had better give up and come home with me,” Gorsuch retorted, defiant to the last.

Thompson, carrying a revolver, approached Gorsuch and pistol-whipped him across the face, knocking him to the ground. As Gorsuch staggered to his feet, Thompson shot him at point blank range. Other men, some from inside the house and some from the mob, opened fire and riddled the slave owner with bullets and buckshot as he attempted to stand again. For good measure, several women approached his body and mutilated it with corn knives (an action embellished with extravagant detail during the subsequent trials and press coverage). Thus ended a Southron who valued pride over his own life.

Dickinson Gorsuch tried to save his father, only to be blasted in the side with Pinckney’s scatter gun. Bleeding profusely, he dragged himself to a nearby tree for cover as the battle continued; he managed to survive, thanks to a freedman who offered him water and comfort. (Chastened by his experience, Dickinson later urged leniency towards the resisters, praising Parker as “a noble nigger.”) Deputy Kline fired wildly into the crowd, then fled into a cornfield and hid until danger passed. Joshua Gorusch received several blows to the head but managed to escape; as did Dr. Pearce, though he suffered minor wounds to his back and wrist, while his coat was riddled with bullet holes. The others, apparently, scattered without offering any assistance.

In the end, Parker and his allies were triumphant. They defeated an armed posse of slave hunters, killed one and wounded or scattered the rest, at the cost of just two men slightly injured. Still, Parker immediately recognized that they were in trouble; he fled, along with the escape slaves, to New York, seeking help from Frederick Douglass. “The hours they spent at my house were therefore hours of anxiety as well as hours of activity,” Douglass later recalled, arranging for them passage aboard a steamship to Canada. Parker would later settle in Kent County, Ontario and continue writing and advocating for abolition and civil rights until his death in 1891.

Responses to the incident varied. Southerners were predictably furious, threatening secession unless Parker was brought to justice. Maryland Governor Enoch Lowe fumed that “if the Union is to be merely a union of minority slaves to majority tyrants…the sooner it is dissolved the better.” Many Northerners agreed. Horace Greeley, ever equivocal between principle and nonsense, wrote “it is out of the question for fugitives to think of forcibly resisting the authorities…and wrong for them to undertake it,” wondering why Parker hadn’t instead run away. Pennsylvania’s Whig Governor William F. Johnston lost a special election to race-baiting, conservative Democrat William Bigler for refusing to take a firm stand.

Abolitionists, on the other hand, rejoiced. Frederick Douglass enthused that Parker and his men had “inflicted fatal wounds on the fugitive slave bill” and dubbed the clash “the battle for liberty at Christiana.” The Boston Examiner crowed that Parker “only did what any white man would be applauded for doing.” The New York Independent argued that “the framers of the [Fugitive Slave] law…are beginning to discover that men, however abject, who have tasted liberty soon learn to prize it and are ready to defend it.” The legal battle, however, remained unsettled.

At President Millard Fillmore’s directive, a company of Marines from Philadelphia marched into Christiana, with one of their number boasting that “we are going to arrest every nigger and damned abolitionist” in Lancaster County. With Parker and the other escapees no longer in town, the Leathernecks settled for arresting dozens of freedmen and white Quakers without bothering to clarify their guilt or innocence. Ultimately, forty-one men (thirty-six blacks and five whites) were indicted, not for attempted murder or rioting, but for treason – the largest single treason indictment in American history.

Ultimately, virtually all the cases were dismissed in preliminary hearings; far more men were indicted than actually participated in the riot. Only Caster Hanway, the hapless Quaker who’d tried to diffuse the riot, endured a formal trial, absurdly framed as the riot’s ringleader. Among his attorneys was Thaddeus Stevens, the abolitionist congressman who defended Hanway with his customary sulfurous wit. He thundered against “professional dealers in human flesh” like Gorsuch while showing the charges against Hanway himself were baseless. Presented with Stevens’ righteous bombast, it took the jury only fifteen minutes to acquit Hanway.

Contemporary Americans recognized the importance of Christiana. “No single event before John Brown’s Raid,” says historian Thomas P. Slaughter, “contributed more to the decline of confidence in the nation’s ability to resolve the controversy over slavery without wholesale resort to arms.” William Parker’s actions inspired additional mass resistance, like the rescue of William Harry by an antislavery mob in Syracuse, New York a month later, and legal actions to forestall recapture throughout the North. Despite this, and continued slave escapes, the Fugitive Slave Law took its toll, with 332 slaves recaptured and repatriated south between 1850 and 1861.

Still, more dramatic events soon overtook Christiana: the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which obliterated the Missouri Compromise and led to instant bloodshed in “Bleeding Kansas”; the Dred Scott decision, which nullified black rights altogether; the caning of Charles Sumner on the Senate floor; John Brown’s Harper’s Ferry raid; and finally, Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860. Together they show a nation tearing itself apart over an issue it refused to settle. Meanwhile African-Americans, from William Parker and Frederick Douglass to the United States Colored Troops in the Civil War, to millions of forgotten men, women and children, slave and free, chose to confront slavery on their own terms.

Sources and Further Reading

The definitive modern account of Christiana is Thomas P. Slaughter’s Bloody Dawn: The Christiana Riot and Racial Violence in the Antebellum North (1991). Other sources consulted include Margaret Hope Bacon, Rebellion at Christiana (1975); Eric Foner, Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad (2015); Jonathan Katz, Resistance at Christiana (1974); and Brenda Wineapple, Ecstatic Nation: Confidence, Crisis and Compromise, 1848-1877 (2013).

You must be logged in to post a comment.