Part Four in a series; see Parts One, Two and Three.

Following the XYZ Affair, war between the United States and France seemed inevitable. Diplomatic stalemate intensified French attacks on American shipping, triggering a vigorous response from American naval vessels. On July 7th, 1798, the USS Delaware, commanded by Stephen Decatur (later famous for fighting Tripoli’s Barbary Pirates), engaged the French privateer La Croyable off Great Egg Harbor, New Jersey. After a brief exchange of cannon fire, the outgunned French warship surrendered to Decatur, who triumphantly brought it and its crew into Philadelphia. “The French have been making war on us for a long time,” Decatur commented; “now we find it necessary to take care of ourselves.”

This action precipitated a state of naval conflict, which raged along the Atlantic seaboard and into the Caribbean, between American and French warships. The Americans generally had the better of the combat, losing only a single ship to at least a dozen French vessels in two years of fighting. Still, there was never an overt declaration of war between France and America. This ambiguity confused and infuriated most Americans, with Rufus King, Minister to London complaining that “Congress have left the country neither in peace nor in war.”

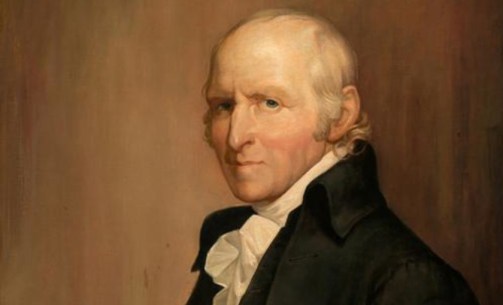

Into this murky situation stepped the sad, strange figure of George Logan. A physician, Quaker and leading Republican in Philadelphia, Logan adamantly opposed the President’s military preparations and complained that under Federalism “Americans…have bartered their domestic rights, liberty and equality for the energy of government and the etiquette of a court.” With Adams’ peacemaking efforts evidently abandoned, Logan stepped into the void, undertaking a private peace mission to resolve what people now deemed the “Quasi-War.”

Logan arrived in Hamburg on August 7th, 1798, shortly after Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts and Franco-American naval clashes began in earnest. Possessing a letter of introduction from Thomas Jefferson, Logan traveled to Paris and made contact with numerous diplomats, emigres and European allies, from the Marquis de Lafayette to inventor Robert Fulton, then living in a menage-a-trois with businessman Joel Barlow and Barlow’s wife, Ruth. With the assistance of Tadeusz Kosciuszko, a Polish military engineer who’d served in George Washington’s Continental Army, Logan arranged an audience with Talleyrand.

Talleyrand, who had known Logan slightly during his exile in Philadelphia, was noncommittal at first. Logan, however, soon impressed the Frenchman with his sincerity and good will, and after several days’ negotiation Talleyrand offered Logan remarkably generous terms: the cessation of France’s boycott against America, the acceptance of American commissioners for formal negotiations and the release of impressed sailors. Talleyrand’s aide assured the American that “Everything will be done according to [your] wishes.” Exultant, Logan appeared as an honored guest at a dinner with French officials, who drank a toast to “the United States of America, and a speedy restoration of amity between them and France.”

At home, American officials were less impressed. Secretary of State Timothy Pickering sent agents to watch Logan’s home and family, while longtime friends and allies shunned them. Logan’s wife, Deborah, complained that “I experienced what it was to lay under the ban of political excommunication.” Even Thomas Jefferson, attempting to visit Mrs. Logan in her husband’s absence, was forced to take “a circuitous route by the falls of Schuylkill” to avoid detection by Pickering’s agents. These clandestine visits nonetheless earned the notice, and inevitably the ire of William Cobbett, who insinuated that the Vice President and Mrs. Logan engaged in both political subversion and sexual mischief.

Nor did Logan himself receive a warmer welcome. In November 1798, shortly after returning home, he located Pickering in Trenton, New Jersey, which temporarily housed the government as yellow fever ravaged Philadelphia. Pickering impatiently allowed Logan to debrief him on his voyage, then dramatically swiped a stack Logan’s writings and dispatches off his desk. When a nonplussed Logan attempted to present a new letter detailing Talleyrand’s promises, Pickering resorted to insults and intimidation. “It is my duty to inform you that the government does not thank you for what you have done,” the Secretary of State barked, before expelling Logan from his office.

Nevertheless, Logan persisted. He arranged an audience with George Washington, reviewing the troops of the New Army mustering around Philadelphia. The Father of Our Country rebuffed his arguments, insisting that “the spirit of this country would never suffer itself to be injured with impunity by any nation under the Sun.” Undeterred, Logan next met with President Adams, who was even more peremptory than his predecessor. “I suppose if I were to send Mr. Madison or Mr. Giles or Dr. Logan,” Adams roared, pointedly insulting his guest, the French “would receive either of them. But I’ll do no such thing; I’ll send whom I please.” With America’s leaders unwilling to listen to Logan, the Quaker’s initiative collapsed.

Ultimately, Congress and the President punished Logan for his peacemaking efforts. On December 12th, 1798, Adams gave a fiery address to the Senate, flanked by Washington and Hamilton (both wearing military uniform) and with British and Portuguese diplomats in attendance. Without mentioning Logan by name, he attacked “the officious interference of individuals without public character or authority” in American diplomacy, adding darkly that “it deserves to be considered what that temerity and impertinence…ought not to be inquired into and corrected.”

While the Senate opted not to prosecute Logan under the Alien and Sedition Acts, they did opt to forestall any similar initiatives. Roger Griswold, the Connecticut Federalist who had so ingloriously brawled with Nathaniel Lyon several months prior, introduced legislation to outlaw private diplomacy; the bill was passed on December 26th, 1798 and signed into law a month later. To this day, the Logan Act nominally bans private negotiations between American citizens and foreign governments (in practice, however, it has rarely been enforced).

Such was the perilous state of American diplomacy. John Adams showed a distressing willingness to rattle sabers and stoke militarist sentiments, in both his public speeches and written correspondence. Yet he always stopped just short of committing America to war. By this time, however, the High Federalists seemed to view war as not only a necessity, but a desirable purgative for American society.

On the French side, Foreign Minister Talleyrand didn’t seem to appreciate the furor caused by his peremptory treatment of the American diplomats. “France…never thought of making war against [the United States],” he insisted, “and every contrary supposition is an insult to common sense.” Embroiled in a huge continental war with Britain, Austria, Prussia and other powers (as Talleyrand made these comments, Napoleon reeled from his naval defeat at the Battle of the Nile), France had no interest in fighting a far-away war with the United States, however weak the new country’s armies may be.

Elbridge Gerry, the last of the Marshall delegation to leave Paris, continually urged Adams to reconsider his hard line stance. An eccentric Massachusetts native, Gerry wasn’t fully trusted by either party, and the Federalists came to loathe him. Timothy Pickering commented that if the French “would … guillotine Mr. Gerry they would do a favor to this country.” Other, less elevated Federalists intimidated Gerry’s family by hanging him in effigy or erecting bloodstained guillotines outside his children’s windows. So toxic had the atmosphere become that even a hint of diplomatic nicety spurred threats of violence.

For the moment, Adams seemed more inclined to listen to Gerry than his naysayers. In January 1799, the President instructed Pickering to draft peace terms for a future rapprochement with France. Then he appointed William Vans Murray as Minister to France, encouraging him to treat with Talleyrand for “tranquility upon just and honorable terms.” The French regarded Adams’ overtures warily but accepted Murray; however, his efforts proved no more fruitful than his predecessors.

Not everyone was pleased with the President’s continued attempts at diplomacy. Secretary of War James McHenry worried that Adams’ peace efforts were “an apple of discord to the Federalists.” (When Adams sent his next peace mission in November 1799, headed by Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth, he didn’t bother consulting with Pickering, McHenry or other cabinet members.) Within the next two years, these fissures would cause the Federalist Party to self-destruct in spectacular fashion.

Their efforts at provoking war momentarily frustrated, Federalists like McHenry had to content themselves with suppressing dissidents. Therefore, Republicans in New England were harassed and arrested for erecting liberty poles; two Connecticut youths receive several week’s imprisonment for heckling a pro-Adams speaker; New Jerseyite Luther Baldwin made a coarse, drunken joke about cannons shooting the President’s ass, earning him a six month jail sentence. Finally, in March 1799, a loose, angry collective of Pennsylvania Germans appeared, at last, to justify fears of incipient civil war.

Fries’ Rebellion started in Bucks and Northampton Counties, in response to Federal efforts at levying property taxes. Virtually all of the rebels were German Kirchenleute, farmers of Lutheran or Reformed religion. Their nominal leader, John Fries, was a Welsh-born auctioneer who had helped suppress the Whiskey Rebellion several years earlier. Yet Fries only joined the rebellion after it was under way; in fact, the rebels counted many leaders, most German, all given to overheated insults and belligerent actions. Henry Ohl, a militiaman in Heidelberg Township, warned a hapless assessor that the Germans would “cut him to pieces and make sausages of him” before paying the new tax. Others menaced officials with rocks and clubs or doused them with scalding water.

The confrontation came to a head when US Marshal William Nichols appeared with warrants to arrest recalcitrant Kirchenleute, keeping his prisoners at the Sun Inn in Bethlehem. On March 12th, 1799 Fries, wearing a military uniform with a black Federalist cockade, helped lead about 140 militiamen armed and marching under fife and drum, into town to affect their release. Vowing “we shall never submit to the law,” Fries nonetheless restrained his men from violence, and negotiated the peaceful release of Nichols’ prisoners. Within a few days, the militia dispersed, sparing Nichols and the assessors further resistance.

Compared to the Whiskey Rebellion a few years prior, Fries’ Rebellion was a non-event. There was pageantry, tension and heated rhetoric exchanged between the tax collectors, the US Marshal and Fries’ rebels. But there was little violence or property damage, aside from a tax collector flogged by the mob and a “rebel” whose hat was shot by a trigger-happy militiaman, and no actual bloodshed. Further, after negotiating the prisoners’ release, the rebels dispersed without further incident. In modern terms, it was far more of a mass protest than an uprising, or even a riot.

Such distinctions were lost on Federalists, who quickly branded the incident a nascent revolution. John Fenno, in the Gazette of the United States, wrote that “about the same time that a pair of emissaries arrived in Charleston from the French Directory, the sans culottes of Northampton raised the standard of rebellion.” President Adams slurred the Kirchenleute as being “as ignorant of our language as they were of our laws.” Weighing a response, Hamilton insisted that “whenever the Government appears in arms, it ought to appear like a Hercules and inspire respect by the display of strength.” Thus he wasted no time in dispatching 2,000 militia and regular troops to suppress the rebellion.

Finding no one to fight, the Federalists sought satisfaction otherwise. Fries and two other leaders were arrested and swiftly charged with treason. In May 1799, at a trial overseen by Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase, the rebels were found guilty and sentenced to hang. After a long, agonized debate, over the opposition of his cabinet, Adams decided to pardon Fries and his compatriots in May 1800. Timothy Pickering, soon to be dismissed from office, complained that Adams’ leniency was “an outrage on decency, propriety, justice and sound policy.” The President felt that executing men for a bloodless protest went too far; evidently, many Federalists disagreed.

Even this miserable exercise in petty repression strained the military. The New Army could only muster about 3,000 men, most suffering from poor clothes, outdated weapons, inadequate supplies, antiquated officers and slapdash training. General Washington complained that Army recruiters attracted “none but the riff-raff of the country, and the scape gallows of the large cities.” Congress, ostensibly eager for war, dragged their feet in funding Washington’s force, while James McHenry’s inept management further hindered military organization. Only Hamilton’s constant attentions as Inspector General infused the Army with energy, organization and morale, and even he could only do so much.

Long after Fries’ pitiful “rebellion” petered out, Federalists entertained fears that Republicans would initiate armed resistance to their program, whether in concert with France or of their own accord. Such fears, while exaggerated, weren’t entirely unfounded. In fall of 1798 Thomas Jefferson and James Madison helped draft the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, insisting that states had the right to defy unconstitutional Federal laws. Madison’s Virginia Resolution was particularly explicit in claiming:

“the powers of the federal government as resulting from the compact to which the states are parties, as limited by the plain sense and intention of the instrument constituting that compact, as no further valid than they are authorized by the grants enumerated in that compact; and that, in case of a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of other powers, not granted by the said compact, the states, who are parties thereto, have the right, and are in duty bound, to interpose, for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining, within their respective limits, the authorities, rights and liberties, appertaining to them.”

Many Federalists expressed horror that such defiance might trigger civil war. (Indeed, later states’ rights extremists – the South Carolina nullifiers of the 1830s, the Confederate States of America, segregationists opposing Brown vs. Board of Education – often adopted Jefferson and Madison’s words for their own purposes.) Alexander Hamilton, on the other hand, welcomed their defiance. He suggested sending the Army to Virginia, “then let measures be taken to act upon the laws and put Virginia to the Test of resistance.”

These military shortcomings and internal divisions didn’t keep Federalists, and Hamilton most of all, from entertaining dreams of military glory and American empire. While General Washington prudently insisted on defensive measures, and President Adams encouraged naval build-up over a costly army, Hamilton couldn’t stop conjuring then-improbable visions of American expansion. Not only were the adjacent territories of Spanish Florida and Louisiana potential targets, along with encouragement of Haiti’s slave rebellion in the Caribbean; Hamilton’s ambitions spread even further afield.

“If universal empire is to be the pursuit of France,” Hamilton mused, “what can tend to defeat their purposes better than to detach South America from Spain?” In furtherance of these designs, he enlisted Venezuelan freebooter Francisco de Miranda to foment a popular uprising in concert with an American invasion force, while coaxing the British into offering naval support. Through Rufus King, the American Minister in London, Hamilton enthusiastically conveyed his plans to Prime Minister William Pitt. Pitt entertained the idea (he hoped to make New Orleans a British stronghold), but ultimately these negotiations came to nothing.

John Adams became livid when he learned of Hamilton’s bizarre scheme. He mocked the Hamilton-Miranda conspiracy “as visionary…as an excursion to the Moon in a cart drawn by geese.” Having exploited American Francophobia and war fever for political benefit, Adams finally recognized the dangers of the forces he played with. In his last year in office, despite (or perhaps because of) the oncoming election, Adams redoubled his efforts at peace. The American Reign of Terror, however, hadn’t yet run its course.

Part Five will conclude the series by examining Adams’ feud with Hamilton and the High Federalists, the Election of 1800 and the prosecution of James T. Callender.

You must be logged in to post a comment.